|

Catch Zero

What can be done as marine ecosystems face a deepening crisis?

Ben Harder

Science News Online

Give a man a fish, goes the Chinese proverb, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime. If he catches too many fish, however, he may leave few fish behind for his children's table. It has taken less than a generation for modern industrial-scale fishing, once it's deployed in an ocean area, to exhaust the vast majority of that area's edible bounty. These massive harvests have left behind devastated ecosystems and depleted economic opportunities.

GONE FISHING.

Fish such as these bluefin tuna,

caught off Nova Scotia in 1935, were several

times more abundant then than they are now.

Ed Pritchard,

http://www.AntiqueFishingReels.com

"There's no place in the ocean left where there are undisturbed fish stocks," says ecologist Boris Worm of the Institute for Marine Science in Kiel, Germany. "The whole ocean has been transformed."

For species after species, in sea after sea, the 20th-century juggernaut of commercial fishing swiftly thinned marine life to a fraction of what it otherwise would be, Worm and Ransom A. Myers of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, report in the May 15 Nature.

More than just documenting what the seas have lost, their analysis and other recent studies hint at the enduring economic costs of mismanaging marine resources. Unless governments take immediate, dramatic steps to curtail overfishing and undo the damage that's been done, swathes of ocean may be rendered practically barren, scientists warn with increasing urgency. Although corrective measures would mean lost revenue and fewer jobs in the near term, the long-term payoffs would be substantial, researchers predict.

For fisheries—the commercial operations that harvest wild fish—to reach those promised waters, however, they'll need to first navigate a maze of political and economic straits. Fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver contends that governments need to overhaul the way they manage activities in the deep seas, as well as along coasts and watersheds that can affect marine ecosystems. The creation of marine areas, in which fishing is banned, and the reduction of fishing elsewhere are among the most essential steps, Pauly says.

When fisheries extract seafood from a region of the sea, they necessarily reduce marine biomass. To a point, that can actually help a fishery, Myers says. That's because the remaining fish enjoy more resources and thus grow and reproduce more rapidly than they would in a crowded natural ecosystem.

For most species, Myers says, sustainable yield is greatest when a stock is at about half its natural size—that is, the size it would be in the absence of industrial fishing. At lesser densities, populations replenish themselves more gradually, and the quantities of fish that can be harvested each year without further diminishing stocks shrink accordingly.

Archived fishing records indicate that most fish stocks now lie well below the size that would produce maximum sustainable yield. Myers and Worm collected raw data from historical sources that chronicled catches from many fisheries dating back to the 1950s. To obtain comparable measurements for fisheries operating at different times and places, the researchers calculated the average number of fish caught per 100 hooks set by boats that spool out and then reel in miles of baited lines.

At the advent of intensive commercial fishing, Myers and Worm found, most fleets caught 6 to 12 fish per 100 hooks. But in every fishery the researchers studied, the number of catches declined by about 16 percent per year. Within a decade, most fleets caught only about 1 fish per 100 hooks.

"Industrialized fisheries typically reduced community biomass by 80 percent within less than 15 years of exploitation," Myers and Worm assert. Moreover, they say, "the global ocean has lost more than 90 percent of large predatory fishes.” Those species include tuna, swordfish, and others traditionally favoured by chefs and gourmets.

In a separate study in the Jan. 17 Science, Worm, Myers, and their colleagues reported that northwest Atlantic populations of three predatory shark species have declined, because of fishing, by more than 75 percent over the past 15 years. Numerous other shark stocks have also suffered substantial losses, the researchers report.

Emptying the tank

Long after some fish stocks sank below their maximally productive sizes, fisheries' hauls continued to rise, says Pauly. As certain fishes became rare and individual fisheries - such as those that harvest California's sardines and New England's cod - collapsed, commercial fishers turned their attentions elsewhere. The discovery of more abundant fish stocks in less exploited waters masked for decades the falling yields of populations and species.

"For a long time, the rate of discovery offset the rate of depletion.” Pauly says.

Growing fleets, government subsidies, larger investments in fuel, and improvements in the gear and techniques used to find and catch fish also helped maintain high global catches. Between 1950 and 1988, total annual fish catches reported to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) grew from 19.2 million metric tons to a peak of 88.6 million metric tons.

The late 1980s marked the turning point. By then, the fisheries mounting efforts to find and catch new fish could no longer compensate for the oceans' waning productivity. The global fish catch has been falling ever since, Pauly has estimated (SN: 12/1/01, p. 343: Available to subscribers at http://www.sciencenews.org/20011201/fob7.asp).

Along with causing the decline in fish populations, modern fishing techniques have also been altering the seas' ecosystems. Skimming large and medium-size fish off the top of oceanic food webs has left a disproportionate fraction of marine biomass at the lower end of the "pyramid of life," says Pauly. This end of the food web includes crustaceans and small fish, as well as phytoplankton and other microorganisms.

"Fishing down the food web is an ecological disaster," Pauly maintains. As ecosystems become bottom-heavy, those larger fish still in the game depend increasingly on smaller and smaller organisms. Since the seasonal abundance of small fish and tiny organisms fluctuates more than that of organisms higher in the food web, the "flattening" of food webs exposes large fish to unusually extreme variations in their food supply, Pauly says. That, in turn, makes their populations less stable and more susceptible to environmental or climatic changes.

Fishing down marine food webs elicits market effects that disguise the consequences of overfishing, Pauly says. Scarcity makes rare species expensive and economically props up fisheries even as their resources erode. For example, he says, stocks of bluefin tuna are "abysmally low," but a single fish can fetch $40,000 in Japan. "[The bluefin's] enormous price essentially dooms it," says Pauly. "The fishery . . . will be profitable to the last fish," he adds.

Fisheries affect more marine animals than just those they aim to catch. Tuna boats, for example, often kill sharks, turtles, and dolphins that get trapped in their nets. Such casualties of fishing, called bycatch, may pare down populations of vulnerable species even if targeted species in the same waters are managed for sustainable yield, says Worm. If fisheries managers consider only the abundance of targeted fishes, he says, they'll "lose the sensitive species in the long run.” And that could lead to ecological changes that end up affecting the targeted species.

Even as fish stocks dwindle, demand is growing. Health researchers have produced countless studies on the benefits of eating fish - especially those rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as tuna and swordfish. Consequently, many health-conscious people have increased their fish consumption.

At the same time, coastal populations of people who rely on fish for their protein are burgeoning around the globe, says Lester R. Brown of the Earth Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. Yet the capacity of the oceans to meet the world's demand for protein has "hit the wall," says Brown.

There are plenty of insults that can add to this injury. For example, Brown predicts that recent shortfalls in global grain production will soon force buyers to bid up prices for that basic commodity and substantially raise prices for many farm-derived foods. Those higher prices could increase demand for oceanic fish and put added pressure on fisheries.

Catching on

The problems with fisheries may run deep, but the remedy is practically jumping into the boat. Regardless of how it's achieved, says Worm, the overriding requirement is to reduce fishing.

"The solution is simple," he says. "The question is how do you get there."

Pauly and Jay Maclean, an independent marine biologist in the Philippines, suggest several approaches to transforming the management of fisheries in their book, In a Perfect Ocean (2002, Island Press).

The book describes one crucial tactic available to fisheries managers - one that Worm and others also advocate: Limit the number and type of fish that fisheries may remove from a region. For example, seasonal quotas on halibut in Alaskan waters helped those fish recover in the 1990s. Since harvesting these bottom dwellers damages seafloor habitat, the quotas also helped other fish stocks in the region recover, Worm says.

Another essential step, say Pauly and Maclean, is to prohibit fishing in large areas of the ocean, especially those rich in fish nurseries. Such no-take zones can serve as refuges for breeding and immature fish, they say.

Experience supports the value of no-take zones, says Worm. Following years of unrelenting declines in cod, haddock, halibut, and other species on George's Bank in the northwest Atlantic, fleets agreed in 1993 to cease harvesting fish in a portion of those waters. "All the stocks . . . rebounded much more quickly than people anticipated," Worm says.

Most of the marine sanctuaries in the United States, however, are not true no-take areas. Some allow fishing on a limited scale, as well as recreational boating, diving, mining, and other activities that could disturb sea life (SN: 4/28/01, p. 264: Available to subscribers at http://www.sciencenews.org/20010428/bob8.asp).

Pauly and Maclean also recommend that governments transform the management of fisheries. Steps would include cracking down on illegal fishing, reeling in those operations that overfish waters far from their home bases, and reducing the scale of fishing fleets, perhaps by buying and destroying vessels or providing fishers with tax breaks or other incentives to take boats out of the water.

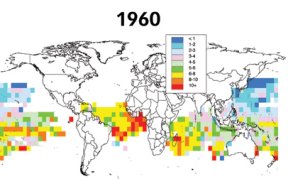

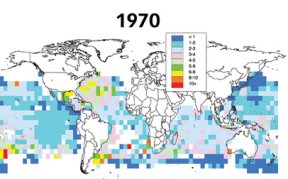

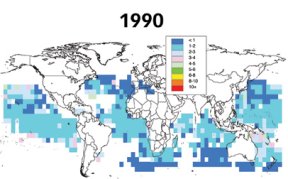

NET LOSS.

Charts show how industrial fishing vessels

have caught fewer and fewer fish per

100 hooks set out. Areas yielding high

catches, indicated by warm colours,

were abundant in 1960...

A consensus is building. An alliance of professional fishers, marine scientists, and former elected officials working for the Pew Oceans Commission released a report on June 4 that calls for national political action to protect and restore marine productivity. The commission called for a network of no-take zones in U.S. waters, steps to monitor and limit bycatch and marine habitat destruction, and new national and regional agencies to manage marine resources and regulate fishing activity.

The Pew report's ultimate impact may

depend on the degree to which a report

commissioned by the U.S. Government

and due later this year seconds its proposals,

says Worm.

|