|

Navy sonar exercises under fire over potential effects on whales

By Mark Kaufman - The Washington Post

The Garden Island

12th July 2004

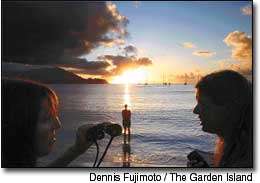

A rare glimpse: Gretchen Johnson (right),

a volunteer with the Hawaiian Islands

Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary,

shares her binoculars with a spectator for a

closer glimpse of the pod of melon-headed whales

gathered offshore in Hanalei Bay Fourth of July weekend.

Residents of Hanalei Bay woke up Fourth of July weekend to a distressing sight: As many as 200 melon-headed whales, a small and sociable species that usually stays in deep waters, were swimming in a tight circle as close as 100 feet from the beach, showing clear signs of stress.

To keep the animals from beaching, the locals kept a vigil all day and through the night, until a flotilla of kayaks and outrigger canoes could be assembled to herd the animals back out to sea, in what was described as a "reverse-hukilau.” So far, only one young whale has been found dead.

But among increasingly worried whale advocates and researchers, the event set off immediate alarm bells: Melon-headed whales are not known to beach themselves, and nothing like this mass stranding close call has occurred in Hawai‘i for 150 years.

Attention quickly focused on the Navy and its use of active sonar — a wall of sound sent out to find underwater objects that can reach the decibel levels of a jet engine. Sonar has been implicated in several recent mass whale-strandings around the world, and the latest research has strengthened the association and suggested that the actual number of incidents may be far greater than anyone realized. The most recent study found that over the past 40 years, mass strandings of the most noise-sensitive whales off Japan occurred repeatedly in the waters near an American naval base, but were unknown in comparable areas elsewhere.

Several hours after the Hanalei Bay episode began, locals learned that a six-ship Navy fleet 20 miles out to sea had begun a sonar exercise the morning that the melon-headed whales headed toward shore. Officials at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration said it is too early to conclusively link sonar to the near-stranding, but they said their top priority is to learn more about the Navy exercise.

Navy officials, for their part, immediately ceased the sonar exercises in waters off the U.S. Navy's Pacific Missile Range Facility at Barking Sands, near Kekaha, part of the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises that continue through the end of this month.

A different kind of sea battle is brewing

Unless a different and convincing explanation can be found, the Hawai‘i incident is destined to become the newest case study in a high-stakes battle between environmentalists and the military over a technology that has been a staple of Navy operations for decades. Marine-mammal advocates say it has become increasingly apparent that sonar can lead to death for whales, porpoises and other sea creatures, and something must be done to limit its toll. But the military says that to protect the nation, it needs to use more sonar, not less. Navy spokesman Jon Yoshishige in Hawai‘i, a Kaua‘i native, said that the fleet does not believe that its sonar had anything to do with the unusual drive to shore of the melon-headed whales. He said that Navy records initially showed that sonar wasn't turned on until about 8.30 a.m. on Saturday, July 3 — an hour after the first reports of whales in Hanalei Bay — but that a full investigation is now underway. He also said the fact that only melon-headed whales were affected suggests that sonar was not the cause, since sonar-induced strandings typically involve a number of species.

Joel Reynolds, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council, which sued the Navy over its plans for a new global sonar system, called the Navy response "consistent with what we've seen in previous instances of strandings close to naval sonar activity — they say ‘We had nothing to do with it.’ Hopefully, a real investigation will determine if that's true or not.” The latest incident could hardly have come at a worse time for the military. A series of congressionally mandated conferences has been underway for months, under the auspices of the Marine Mammal Commission, to assess the effects of sonar and other underwater noise on whales, porpoises and dolphins, and the group is expected to make recommendations to NOAA and Congress next year.

|